ARTICLE: hundrED | Global Oneness Project

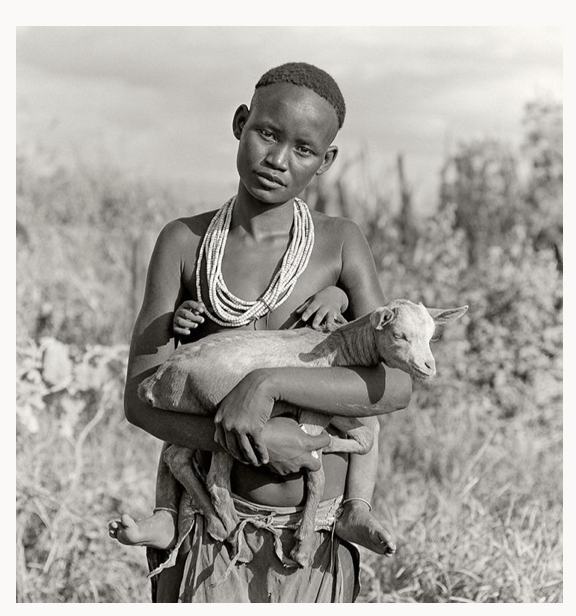

Image by Jane Baldwin for Global Oneness Project

Cultures around the world are vanishing at a rapid rate. Unique forms of cultural knowledge—language, myths and stories, rituals, music, artifacts, traditional dress, and unique agricultural methods—are at risk. According to UNESCO, half of the languages spoken today will disappear if nothing is done to preserve them.

Why does this matter? Anthropologist Wade Davis, in an interview with National Geographic explains, "As cultures disappear and life becomes more uniform, we as a people and a species, and Earth itself, will be deeply impoverished." Learning what is at risk is essential.

A deeper look at indigenous cultures provides students with an ever-widening window of inquiry. Students discover remote geographical places and cultural artifacts local to various regions, learn about the wisdom and ways of life of indigenous people, and examine the global issues threatening these people and places. Students find themselves in an expanding world where they are witnessing history and can become inspired to examine their own cultural values and heritage.

Asia Society recognizes the following outcomes—investigating the world, recognizing perspectives, and taking action—as indicators of global competence. These strategies, along with resources, offer ways to integrate the study of indigenous cultures into the global learning classroom.

Investigating the World

Cultural museum exhibitions, either in-person or online, provide important opportunities for students to investigate the world. Exhibitions today bridge media with traditional art forms, such as painting and photography, and offer inquiry-based tours for schools and classrooms.

Jane Baldwin, photographer of Kara Women Speak, recently said to me, "As a photographer, I believe art can inform and focus our attention in powerful and insightful ways. Through engagement and conversation, art can inspire empathy and evoke our humanity by raising awareness of political issues and be a catalyst for change."

Kara Women Speak explores the indigenous women and culture of the Omo River Valley and Lake Turkana watershed in Southwestern Ethiopia. The indigenous communities of the region are threatened by upriver hydroelectric power projects and international land grabs. For an interactive exhibit at the Sonoma Valley Art Museum in Northern California, Baldwin produced life-sized portraits, audio recordings of the Kara women, and ambient sounds from the Omo River to provide visitors with a visceral experience.

Brandon Spars, humanities teacher from Sonoma Academy High School, took his freshmen students to the exhibit to gain an understanding of complex projects that have damaging impacts. This fits with the freshmen curriculum, which explores the question, "How does geography shape culture?" The exhibit, Spars explained, was a valuable experience. His students were able to witness an important story, meet the artist, and ask questions.

Cleary Vaughan-Lee

Executive Director of the Global Oneness Project, a free multimedia education platform which hosts documentary films and photography on social, cultural, and environmental issues.

This article was originally published in Education Week and has been reposted on HundrED with the author's permission. Cover image by Taylor Weidman for Global Oneness Project. This article has been abridged.

ARTICLE: NIGRIZIA

ENGLISH TRANSLATION

The Threatened people of the Omo River Valley Ethiopia

Installation at MUDEC in Milan

Con gli occhi delle vittime | Through the eyes of the victims

Nigrizia Italy, II mensile dell’Africa e del Mondo Nero | December 2018

By Stefania Ragusa

Photographs by Jane Baldwin

In Ethiopia, a development project risks wiping out 200,000 people. At the Museum of Cultures, an exhibition tells the point of view of those who resist. An initiative by photographer Jane Baldwin, in collaboration with Studio Azzurro and Survival International.

Enter into the room and immediately be captured by the great terracotta river that “moves” still and sinuous on a long sculptural table. The visitor is invited to take a fragment of that terracotta and to drop it, through a jar, into one of the small bags hanging on the walls. At that point the corresponding screen lights up and the story begins. It may be that of a widow of the Hamar ethnic group, who explains: "This river is like mother's milk for me"; or a Kara woman, who tells how her day always begins with a visit to the river, to get water for coffee; or two young Dassanech, who ask: "Will the river continue to live or will we lose these fertile lands and water in the future?" Or it is summarized in a glance, like that of the adolescent Mursi met in a camp temporary, mounted on the banks in the dry season. The audio of the women’s original voices telling their stories is heard. The screen reveals the translations and images emerge gradually from the darkness, to be defined in vivid black and white portraits. It is a suggestive modality that emphasizes the centrality of people: those who are rarely given a voice and under normal conditions no one would care. But today their life is threatened.

The river we are talking about is the Omo, which is born in the Ethiopian plateau and, after a journey of about 800 kilometers, flows into Kenya, the lake Turkana since last June included among the endangered heritage of humanity. Hamar, Kara, Dassanech, Mursi are the peoples who have always lived alongside these waters, in an economy of self-sufficiency and in harmony with the environment. It is at least 200 thousand people. The threat that is looming is the construction of two new dams: after the gigantic Gibe III, completed in 2016, Gibe IV and Gibe V are "expected". In this case, the Italian Salini Impregilo will be the one to realize them.

The objectives? To increase the production of energy and its commercial sorting, to convert the land to intensive agriculture. A combination that will bring great gains and great evils: not only the end of the river's civilizations, but also the destruction of the extraordinary ecosystem of which the Kara and the others

have been custodians until today, as well as the opening to the notorious land grabbing.

‘If the only thing left to speak is the river’ Jane Baldwin, an American photographer and activist, traveled for ten years in the Omo Valley, photographing women and collecting their testimonies. In collaboration with the Studio Azzurro research group, who created this multimedia installation, with an evocative and eloquent title, which mixes in a narrative framework photography, video, fine art, information and poetry. If talking only the river, in a few essential steps, brings us into the point of view of the "victims": treated with hardness and sufficiency by the government, ignored in their essential requests, aware but not resigned.

"With my art, I want to draw attention to the threats facing the people of Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley and Kenya’s Lake Turkana,” explains Baldwin, “My hope is that this installation will increase awareness and instill empathy, awakening our humanity to the issues facing the peoples of this region face.”

"Like all the Indigenous peoples of the world, even the Indigenous people of Ethiopia’s Valle dell Omo are threatened by racism, theft of land, forced development and genocidal violence,” echoed Francesca Casella, who heads the Italian section of the non-governmental organization Survival International, engaged for almost 50 years in the fight against the extermination of indigenous peoples and present in the project. “We hope that this immersive experience will encourage the visitor to participate in the battle against one of the most urgent and gruesome humanitarian crises of our time.”

‘If Only The River Remains to Speak’ is hosted until 6 January 2019 at MUDEC, the Milanese Museum of Cultures. You do not have to pay the ticket and the visitor can, if he wishes, take with him, as a souvenir and memento, a small piece of terracotta, a symbolic fragment of the Omo.

ARTICLE: Con gli occhi delle vittime | Through the eyes of the victims

Con gli occhi delle vittime | Through the eyes of the victims

Stefania Ragusa for Nigrizia Magazine

December 2018

In Ethiopia, a development project risks wiping out 200,000 people. At the Museo delle Culture, an exhibition tells the point of view of those who resist. An initiative by photographer Jane Baldwin, in collaboration with Studio Azzurro and Survival International.

Read article with translation here

ARTICLE: Only the River Remains to Speak, Archi.Media Trust, Grosseto, Italy

Hamar girl ©Jane Baldwin

Only the River Remains to Speak. Multimedia exhibition to promote and support the rights and cause of the Lower Omo Valley indigenous peoples

Archi.Media | September 27, 2017

“I have one question for you – what I am asking is – is this river, where we plant our food, where we catch our fish, will this continue or will we lose this farming land and water for the future? If you know, will you share with me? We have no say. Nobody comes and explains to us. We have no future.” – Houtil Naranya, Dassanech matriarch, Kara Women Speak

The cooperation between Jane Baldwin, Studio Azzurro Produzioni, Survival International (Italy) and Archi.Media Trust Onlus for the creation of this multimedia exhibition was developed from the common will to give voice to the peoples of the Omo Valley and Lake Turkana, in Ethiopia and Kenya, and to enlighten the environmental and human rights issues that threaten them.

At the core of this advocacy initiative is photographer Jane Baldwin’s work Kara Women Speak, a project that represents over ten years of field-research, documenting the women of the Omo in their own voices and capturing the stories of issues that threaten their communities. With the cooperation of Studio Azzurro and the consultancy of Survival International (Italy), the images, the voices and the testimonies collected by Baldwin were edited and rendered in the multimedia, sensory rich and interactive exhibition Only the River Remains to Speak: a dense and compelling journey, combining the potential of new digital technologies with the materiality of raw matters, surfaces and objects, making them receptive and reactive to the gestures of the visitors.

Aim of exhibition is telling a present-day story of a river and of the peoples that it sustains, narrated in their own voices, to raise awareness about the violations of tribal peoples’ human rights, calling for the protection of their ancestral knowledge and ways of life. Only the River Remains to Speak was exhibited from 1 October 2018 to 6 January 2019 at the Museum of Cultures – MUDEC of Milan.

INTERVIEW: VOGUE Italia

“Se a parlare non resta che il fiume” is a multisensory installation that combines the artwork of American photographer and educator Jane Baldwin with the creativity of the renowned Milanese art research group Studio Azzurro, founded in Milan in 1982. The installation is dedicated to the tribes of the Omo Valley, whose ecosystem and the people who depend on it have been threatened by a huge hydroelectric project made in Italy, and by the land grabbing that followed by agro-industrial farmers who want to grow cotton and sugarcane crops for export, and it is built as an interactive poetic journey along the Omo River where visitors engage with the women, who are the main characters of the project and the depositaries of oral traditions through tales, myth and song.

Immersed in the sounds of a flowing river, a metaphorical sculpture of red clay symbolizes the Omo River’s meandering course. The red, desiccated surface of the river indicates the crumbling and dried up riverbed, deprived of its annual flood by a controversial development project. The visitor transforms a clay fragment into an amulet that is dropped into a receptacle, tranforming the river into a storyteller, the voice of the river becomes the voices of the women.

The multisensory installation at MUDEC – Museo delle Culture, within the “Geografie del Futuro” program, will last until January 6, 2019.

We interviewed Jane Baldwin, American artist and educator who uses photography and audio recordings as a practice of documentation, research and storytelling.

When did you start to work systematically on the Omo River Valley area? What brought you there?

I first learned of Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley from a friend and colleague who had just returned from her travels in Africa in 2004. My first visit to the region was in 2005. Initially, I traveled as a photographer. I returned annually to the region between 2005-2014 to document women’s stories in their own voices. The project slowly evolved into a multi-sensory, immersive body of work about women, culture, human rights and the environmental issues that threaten the communities of Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley and Kenya’s Lake Turkana watershed. My advocacy for the human rights and environmental concerns of Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley and Kenya’s Lake Turkana developed later.

Why is your work focused in particular on women?

My relationships with the women of the region developed slowly over time. Their societies are patriarchal and gender roles are strictly defined, thus making women’s condition not always easy. Women are the nurturers and sustainers of their communities and families. They are valued for the number of children they bear and for their hard work, but they are seldom engaged for their thoughts and ideas. As a woman, I wanted to give them a voice. They were eager to sit and talk with me about their lives. About what made them happy and their concerns for the future of their communities.

For reasons I can’t explain, when I arrived in the Omo River Valley the land and people felt familiar. I intuitively understood that I had to leave my western sensibilities at home, my ideas of right or wrong or judgment—to learn, I had to listen, free from any stereotype.

My camp was located on Kara ancestral land. Kara women were often in camp walking back and forth between their village and the Omo River to collect water. I noticed that when the women came into camp they’d linger in the background. One day I approached them and we began to sit together, finding ways other than a common language to communicate. With the help of my guide and a young Hamar woman to translate for me, in 2009, I began to interview the women of the Kara, Hamar, Kwegu, Nyangatom, Dassanech and Turkana communities and record their cultural stories and their role within it. Women are the heartbeat of all Omo cultures. They are keepers of their oral traditions that pass down the narratives of their ancestry and families.

This project then evolved into giving ‘voice to the voiceless’— going beyond their portraits. Their stories become a mirror to examine our own ways of looking and ways of seeing, to question our own perceptions and life experiences.

In this project the sound has a fundamental role. How did you realized that this was so important and how did it develop in your project?

I have long been sensitive to the ways that photographers often put their lens on foreign cultures and the “colonial gaze” of western or Eurocentric perceptions that romanticize or judge tribal culture without engaging directly with the people. I’ve written letters to the editor when a foreign photographer or journalist drops into the Omo River cultures for a quick glimpse of the people and then projecting their biases reinforcing stereotypes that are most often misleading or even dangerous. They focus on shock value rather than a fair and respectful eye on their culture. I knew I wanted to do things differently. I first used a recorded audio of a woman’s story in a short film entitled “Kara Women Speak” in 2012, but it was only with the collaboration of Studio Azzurro that all the multimedia elements of my work were brought together and combined into a multi senses and immersive project of great impact as “If only the River remains to speak”. Environmental sounds are an important element for setting the ambience of a space, and the sound of the women’s voices help to communicate the emotion, disposition and intention of the subject.

Tell us something about the collaboration with Studio Azzurro. How did it start?

My colleague encountered Studio Azzurro’s work at the Venice Biennale and she was impressed by their ability to combine technology, design and creativity to create emotionally relevant installations and sensitive environments that react to external incentives. Where storytelling originates by the visitors own gestures. I believe art can inform and focus our attention in powerful and insightful ways. Through engagement and conversation, art can inspire empathy and evoke our humanity by raising awareness of political issues, and be a catalyst for change. Studio Azzurro was definitely the partner I was looking for! After a call and with the help of Survival International – the global movement for tribal peoples – I flew to Milan for a planning meeting in March 2016.

Studio Azzurro led the installation design and managed the construction and technology. Leonardo Sangiorgi envisioned the installation space immediately, which included a 40 foot long riverbed of dry red clay as a metaphor for the dying of the Omo River. Back in California, I finalized the image selection and worked editing the ambient sounds. A thrilling collaboration.

Do we need to use other languages besides the image to speak to people and get closer to them? Is there a kind of limit in photography?

I don’t believe there is a limit to photography—it’s always in transition. However, I believe photographic exhibitions can often be one dimensional. I felt that in order to tap into the consciousness of the viewer it needed to be multisensory and immersive. For this reason, we chose to collaborate with Studio Azzurro whose work creates deep emotional engagement. Visitors often come to the conclusion that the women – as any other tribal people in the world – are just like us, in more ways than they may have originally thought. The added stories have helped increase a sense of shared humanity.

“Se a parlare non resta che il fiume” is a multisensory installation where the viewer is actively engaged in it. How important is it today, in your opinion, the experience in the process of involving people and receiving a message?

The multi-sensory experience is an essential and important part of this project. By using technology and appealing to multiple senses – including tactile activities – our goal is to simulate encounters, bring the stories of the women of the Omo River Valley to life and make visitors have a more profound experience and engage and connect on a deeper level. The entire experience provides a 45-60 minute virtual “visit” able to build a bond with the women of the region and able to help the viewers to break through the emotional exhaustion often experienced when faced with difficult situations, such as environmental or human rights’ violations.

My hope is that this exhibition helps us pause to consider the consequences of our irresponsible use of natural resources around the globe. “Progress can kill” quotes a campaign by Survival International, whose important work I hope will be underlined by the installation, giving it the support it deserves. The combined effect of land grabbing and a huge dam made in Italy is compromising the environmental balance of the Omo basin and undermining the food security of at least 100,000 indigenous people in Ethiopia and 300,000 in Kenya largely self-sufficient. The granaries and the precious pastures of many Kara, Mursi and Hamar villages have been destroyed. The Kwegu, who depend almost exclusively on hunting and fishing, are starving. Many of the communities I have visited have already lost or are losing access to their lands and to the banks of the river. And every opposition is silenced by the Ethiopian government with force and violence. The Ethiopian authorities say they want to “commit to preserving the cultural heritage of these groups (threatened with extinction) through the creation of a museum of the Omo cultures and through ‘cultural villages’ “oriented to tourism”. But “depletion, death and human zoo are too high a price to pay to this alleged ‘progress’ and they are unacceptable”, Francesca Casella, director of the Italian headquarters of Survival (www.survival.it), denounced. “New models of ‘development’ are needed, that do not trample on human rights. Not just for the indigenous peoples, but for all of humanity”. The indigenous peoples of the Omo valley are not primitive and underdeveloped as many want us to believe, they are just different and represent an essential part of the human diversity on which the survival of all of us depends. Both Studio Azzurro and I hope that the installation will instill this awareness in all visitors inspiring them to take part in the change.

SE A PARLARE NON RESTA CHE IL FIUME

Ambiente sensibile per le tribù della Valle dell’Omo

Artistic installation by Studio Azzurro and photographer

Jane Baldwin, in support of Survival International

MUDEC – Museo delle Culture di Milano

1 October 2018 – 6 January 2019

Interview by Rica Cerbarano

ARTICLE: Photo Vogue Festival: Se a parlare non resta che il fiume

Dassanech Girls, Jane Baldwin 2009

Photo Vogue Festival: Se a parlare non resta che il fiume

Rica Cerbarano for Vogue Italia, Milan, Italy

November 15, 2018

Se a parlare non resta che il fiume, is a multi-sensory installation that combines the artwork of American photographer and educator Jane Baldwin with the creativity of the renowned Milanese art research group Studio Azzurro, founded in Milan in 1982. The installation is dedicated to the tribes of the Omo Valley, whose ecosystem and the people who depend on it have been threatened by a huge hydroelectric project made in Italy, and by the land grabbing that followed by agro-industrial farmers who want to grow cotton and sugarcane crops for export […]

Read article here

PRESS RELEASE: FEATURED PHOTO Fisherman at Lake Turkana, Kenya, © Jane Baldwin

Fishermen at Lake Turkana ©Jane Baldwin 2014

UNESCO World Heritage Committee inscribed Kenya’s Lake Turkana as “in danger” over Gibe Dam impacts

Dr. Rudo Sanyanga, Ikal Ang’elei, and Dr. Eugene Simonov for International Rivers

June 27, 2018

Today, the UNESCO World Heritage Committee took the decision to officially inscribe Lake Turkana as a World Heritage site “in danger” because of severe impacts caused by the Gibe 3 Dam, constructed upstream on Ethiopia’s Omo River. The dam and associated sugar plantations have severely restricted flows into Kenya’s Lake Turkana, the world’s largest desert lake.

“We applaud the decision taken by the World Heritage Committee,” states Dr. Rudo Sanyanga, the Africa Director at the non-profit International Rivers, which advocates for the protection of rivers and the rights of people who depend on them. “Ethiopia has knowingly and deliberately jeopardized the viability of Lake Turkana, which serves as a critical lifeline for half a million people in Kenya. This decision is long overdue.”

Kenyan campaigners have led the opposition over the past decade to Ethiopia’s Gibe 3 Dam, which began producing power in 2016. Since then, lake levels have dropped precipitously as Ethiopia fills the dam’s reservoir and diverts the river’s flows toward newly established sugar plantations that require substantial water resources. This has led to significant hardship for the hundreds of thousands of people who subsist off of Lake Turkana, as they have seen fish catches plummet and are facing food insecurity. Further developments upstream could lead to the collapse of local livelihoods.

“The lives of local communities now hang in the balance given that their main sources of livelihood are facing extinction,” says Ikal Ang’elei, Director of Friends of Lake Turkana. “This decision by the UNESCO World Heritage Committee should serve as a notice to Ethiopia to cancel any further dams planned on the Omo River.”

Lake Turkana was previously proposed by UNESCO to be added as a site in danger in 2011, but Ethiopia has repeatedly avoided inscription by promising to conduct a Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Gibe scheme’s impacts. That study has still not begun, even while dam construction continued apace and sugar plantations expanded. Meanwhile, Ethiopia is aggressively pursuing further dam development on the river, having signed a contract with Italian construction firm Salini Impregilo to build an additional dam at the Gibe site, which would only compound the impacts on Lake Turkana.

“This decision represents a serious indictment of the government of Ethiopia, which has for years attempted to downplay the risks and used delaying tactics to prevent what amounts to an official reprimand for its conduct,” adds Ms. Ang’elei.

Lake Turkana joins a long and growing list of World Heritage sites threatened by dam construction. Tanzania’s plans to construct the Stiegler’s Gorge Dam in the Selous Game Reserve, a biodiversity hotspot for African wildlife, has prompted outcry from conservationists over threats to endangered species.

“While Lake Turkana is a glaring example of the impacts that dams have wrought on some of the world’s irreplaceable cultural and biodiversity sites, it has unfortunately become all too common,” says Dr. Eugene Simonov, Coordinator of the Rivers Without Boundaries Coalition. “Despite the precipitous decline in new hydropower globally, nearly a quarter of all natural heritage sites in the world are threatened by water infrastructure such as dams – and this share is rising.”

This concerning trend prompted the World Heritage Committee to pass a resolution in 2016 calling for a ban on dam construction within the boundaries of World Heritage sites, and for proposed dams that may impact World Heritage sites outside their boundaries to be “rigorously assessed.”

As the 42nd session of the UNESCO World Heritage Committee proceeds, civil society requests that the delegates pass a resolution calling for the protection of all World Heritage sites threatened by dams and other infrastructure so that current and future generations can benefit from the valuable natural inheritance upon which we all depend.

PUBLIC PROGRAM: Onassis Foundation, New York, New York, #ISTANDFOR: RIVER ECOSYSTEMS AND WOMEN

Kara, Jane Baldwin, 2005

By Jane Baldwin

I stand for the ecosystems and the women of Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley and Kenya’s Lake Turkana watershed. There is no separation; the women live in harmony with the river and refer to the Omo as their mother and father. The women of this region live in indigenous, patriarchal communities within countries where people lack basic civil rights. The construction of the Gibe III Dam (the largest dam in sub-Saharan Africa), which has displaced people from their ancestral lands without consultation or compensation, brings tragic consequences to all these communities. The people do not have a voice; they are vulnerable and powerless to resist this government-sponsored development. Government land grabs for foreign agricultural investments, together with the mega-dam construction, destroy the natural resources that have been the foundation of their self-sustaining community life.

For ten years I returned annually to Ethiopia to photograph and document the stories of the women of the Omo River Valley. In these patriarchal cultures women rarely have a voice and their stories often go untold. They were eager to talk about their lives and the future of their people. Over time, this evolved into a multi-sensory body of work titled Kara Women Speak | Stories from Women.

I believe that art can be a catalyst for engaging in critical dialogue. Through engagement and conversation, art can inform and focus our attention in potent ways. It can evoke compassion and empathy of our shared humanity by raising awareness of political issues and perhaps inspire change. The power of storytelling brings these women’s stories to life. As we listen to their voices, we begin to hear our own voices; their stories become our stories.

My recent solo multi-sensory museum exhibition Kara Women Speak | Stories from Women featured life-size portraits with accompanying stories told in the women’s own words. The stories spanned the cultural traditions of first and second wife, death and mourning, arranged marriage, childbirth, education, and one woman’s role as the first elected female to be the Kara’s representative to the government. Viewing the portraits and listening to each woman’s voice with it’s own unique inflection within the Museum audio tour guide revealed universal emotions. The visitors left the exhibition with a sense of empathy and understanding of the women, and many returned for the accompanying public programming that discussed the related human rights and environmental issues of the region. The stories in this multi-sensory exhibition humanized the issues and helped to build an emotional bridge between the people visiting the exhibition and the women featured in the photographs.

These stories also raise the general question: When is enough, enough? When will we recognize the wisdom of these ancient civilizations and pristine ecosystems, instead of destroying them in the name of modernization, and work collaboratively to protect them.

ARTICLE: Listening to Kara Women Speak: One Woman’s Journey to the Omo River

Kara dancers, Jane Baldwin, 2007

Listening to Kara Women Speak: One Woman’s Journey to the Omo River

Sarah Bardeen for International Rivers

October 15, 2015

Baldwin spent the next ten years forging a relationship with the Kara people, one of eight distinct indigenous communities in the Lower Omo Valley whose lives and homes are currently threatened by agricultural plantations and Ethiopia’s Gibe III Dam.

ARTICLE: Land Grabbing Becomes a Global Phenomenon | Antony Loewenstein for farmlandgrab.org and New Matilda

Land Grabbing Becomes a Global Phenomenon here

Antony Loewenstein for farmlandgrab.org and New Matilda

July 10, 2015

American photographer Jane Baldwin has been visiting the Omo River for a decade, documenting the gradual erosion of local rights, and she tells me via email that foreign investors threaten “self-sustaining agro-pastoral communities.” A local woman from the Nyangatom tribe, who can’t be named due to threats against her life, says that, “They are taking this river to sell the hydroelectric power. We say to them, if this river is taken from us, we might as well kill ourselves so we won’t starve to death. If you decide to make a dam there, before you start the dam, you better come here and kill us all.

PUBLIC PROGRAM: Kara Women Speak | Lesson Plan

Jane Baldwin's recent body of work titled Kara Women Speak: Stories from Women, distills ten years of travel in the Omo River Valley photographing and recording stories from the women of indigenous communities living in southwestern Ethiopia. The Omo River Valley is home to roughly 12 indigenous cultures that have evolved over hundreds of years. All are intimately connected to the natural world. Oral tradition conveys the narratives of their ancestry and family histories, and women are the keepers of this oral tradition through their storytelling of myth, proverb, and song.

Baldwin's work is an intimate portrayal of the women of the Omo River Valley who have lived for centuries unaffected by colonialism or modernity. Since a woman's point of view is rarely sought in these patriarchal societies, their stories often go untold. Yet, women are the nurturers and sustainers of their families and communities. They are valued for the number of children they bear and their hard work, but their thoughts and ideas are seldom heard. As a witness to the rich cultural lives of these women, Baldwin presents their stories to the outside world with integrity and respect. Her work reveals a sense of the women's strength and dignity, giving voice to their lives and stories, thoughts, and feelings.

Communities along the Omo River, practice flood-recession agriculture and depend on the river's natural flood cycle to replenish their land for farming and grazing of livestock. Ethiopian government contracts have been awarded to foreign construction firms to build hydroelectric dams on the Omo River for energy exports. Gibe III, the largest dam of its kind in sub-Saharan Africa, will drastically alter the river's flow and decrease essential flooding to this fragile ecosystem. Vast tracks of rich farmland have been leased to foreign investors to farm crops for export, forcing indigenous people to abandon their ancestral lands without consultation or compensation. They are possibly the last generation to live according to their culture. The livelihood of all agro-pastoralists living in the Omo River-Lake Turkana watershed is now endangered.

"The human rights concerns and environmental threats to the Omo River Valley-Lake Turkana watershed is urgent," comments Baldwin. "It's my hope this photo essay will encourage interest in the issues facing the people of Lake Turkana and Ethiopia's Omo River Valley. The global drive for dwindling natural resources, and destruction of healthy ecosystems, of water, soil, and air will potentially affect us all." These issues reflect the uncertain fate of all people in the developing world.